Glaciers are constantly on the move. They’re flowing rivers of ice, constantly flowing and fracturing and bulldozing everything in their path. But under the ice there’s a hidden network of “plumbing” – water flowing in channels within and beneath the ice. This liquid water can lubricate the flow of ice over the bedrock, changing the speed at which the ice is moving. For glaciologists, understanding this hidden plumbing is essential for improving forecasts of ice flow and, ultimately, sea level rise.

Cardiff University’s Cryoegg project set out to make those concealed environments measurable in a new way: by placing a compact wireless probe (the “Cryoegg” itself) directly into subglacial water systems, collecting pressure, temperature, and electrical conductivity data, and transmitting readings back up to the surface. The ambition was straightforward; the environment was not.

The Challenge

Subglacial research is defined by constraints. Access often comes through narrow boreholes drilled or melted through ice that is hundreds of meters thick, in places where weather is harsh, logistics are limited, and communications infrastructure is non-existent. Once instruments are down-hole, the borehole can refreeze, and moving ice can deform or destroy anything relying on fixed cables. In many cases, retrieval simply isn’t part of the plan; you have to assume what you deploy may never come back up.

That creates a second, less visible challenge: even if you can get sensor data to the surface, how do you move it off the ice reliably, with minimal power, and without needing someone to stand next to the equipment?

The Work

Cryoegg was developed specifically to reduce reliance on vulnerable wired systems. In peer-reviewed field trials, the team demonstrated wireless transmission through cold ice at substantial depths, with the published work reporting communication through up to 1.3 km of ice under test conditions.

Cryoegg’s design also targets long deployment life by spending most of its time asleep, waking briefly to take readings and transmit them, then returning to low power operation. Some Cryoeggs have now been operating for more than 18 months underneath the ice.

To make that science usable day-to-day, the field system still needs a dependable ‘last mile’ from the glacier surface back to the researchers, so data doesn’t stay stranded in a remote camp until the next field visit.

Getting the Data Home

During a recent field trip to West Greenland, the team deployed a surface datalogger to receive transmissions from equipment buried hundreds of meters below the ice, then forward those messages back to the UK over satellite.

Once you’re operating in environments that are cold, wet, windy, and hard to revisit, reliability and power discipline become operational requirements. The device used by the team to move messages from the datalogger to base was RockBLOCK Plus, a waterproof satellite IoT device designed for short burst messaging via the Iridium network.

For this kind of deployment, the relevant details are simple: it’s built to stay outside, keep working, and do so without demanding much power. RockBLOCK Plus is IP68 rated, and operates in temperatures as low as -40°C to as high as +85°C, with a rugged design intended for remote, unattended installations.

The Result

By pairing a wireless subglacial probe with a robust surface-to-satellite backhaul, the Cryoegg team can focus more of their effort on what matters: collecting measurements that illuminate how water moves beneath ice, and using those observations to improve our understanding of glacier dynamics.

The overall impact is practical as well as scientific. When data can make its way off a glacier without frequent visits or complex infrastructure, projects become more resilient, field seasons become more efficient, and research teams can spend less time babysitting comms and more time interpreting results.

“We’re doing exciting science in a very challenging environment. We needed something that would keep sending data reliably in harsh conditions, and RockBLOCK Plus has done exactly that. The Ground Control team were easy to work with, and I’m looking forward to trying the latest iterations of the hardware in future deployments.”

Dr Mike Prior-Jones, Electronic Engineer and Glaciologist (read more about Dr Prior-Jones)

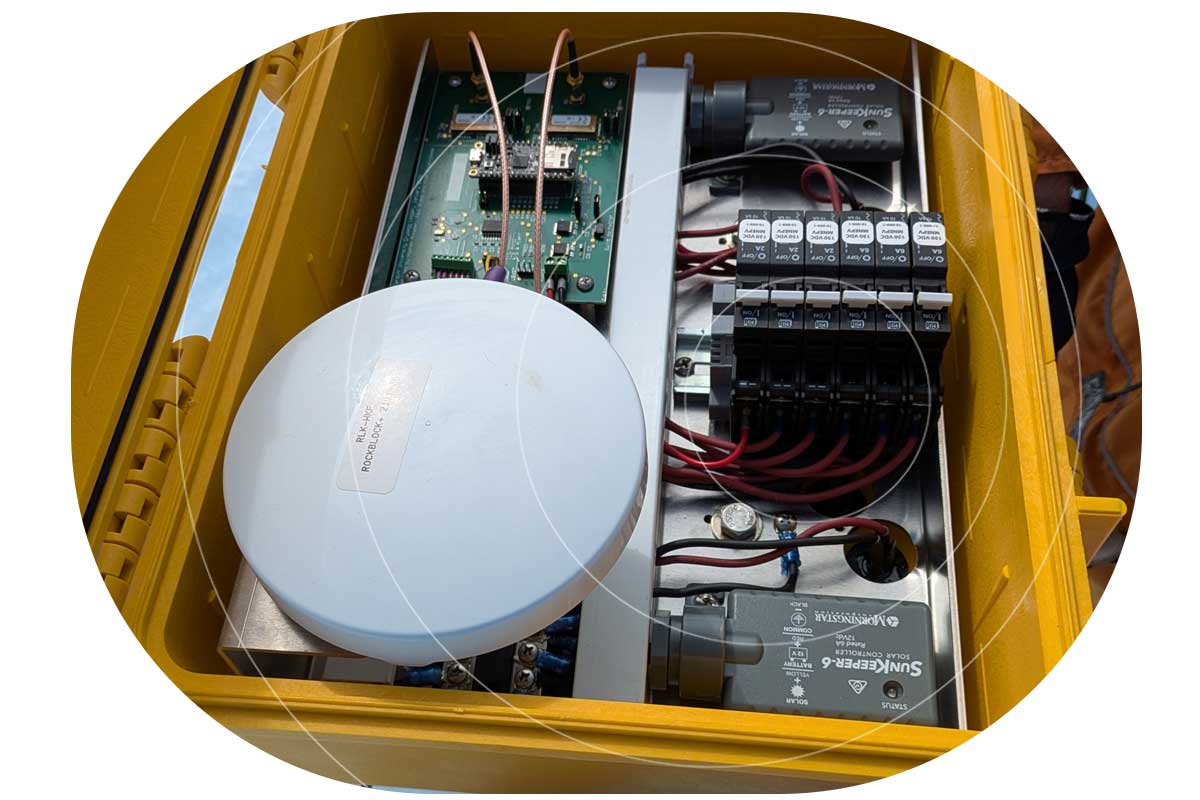

“Inside the datalogger control box, showing the RockBLOCK Plus modem. Although the RockBLOCK Plus is waterproof, we put it inside the box to avoid having to pass a cable through the waterproof box, and it works fine through the plastic box lid.”

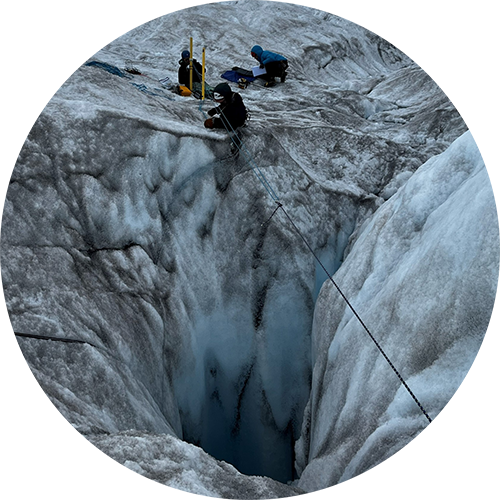

“One of the dataloggers on Isunnguata Sermia, an outlet glacier in West Greenland.”

“The team preparing for a Cryoegg deployment in a moulin (a naturally-occurring hole in the glacier made by meltwater) on Isunnguata Sermia. Jonathan is roped up with a harness in case he falls. The ice here is about 400m thick, and the initial drop into the moulin is probably around 50m, so not something you want to fall into.”

Have data in hard-to-reach places?

Ground Control has over 20 years experience in extracting data from the most remote and inhospitable places on Earth. Our satellite IoT solutions draw very little power, work reliably anywhere with a clear view of the sky (even within a plastic container!), and come in multiple form factors, from developer PCBs to rugged and enclosed devices.

Let us know about your project by emailing hello@groundcontrol.com, or complete the form, and we’ll reply within one working day to offer our expert advice.