Cellular, Proprietary Satellite, and NTN in Remote Environmental Monitoring

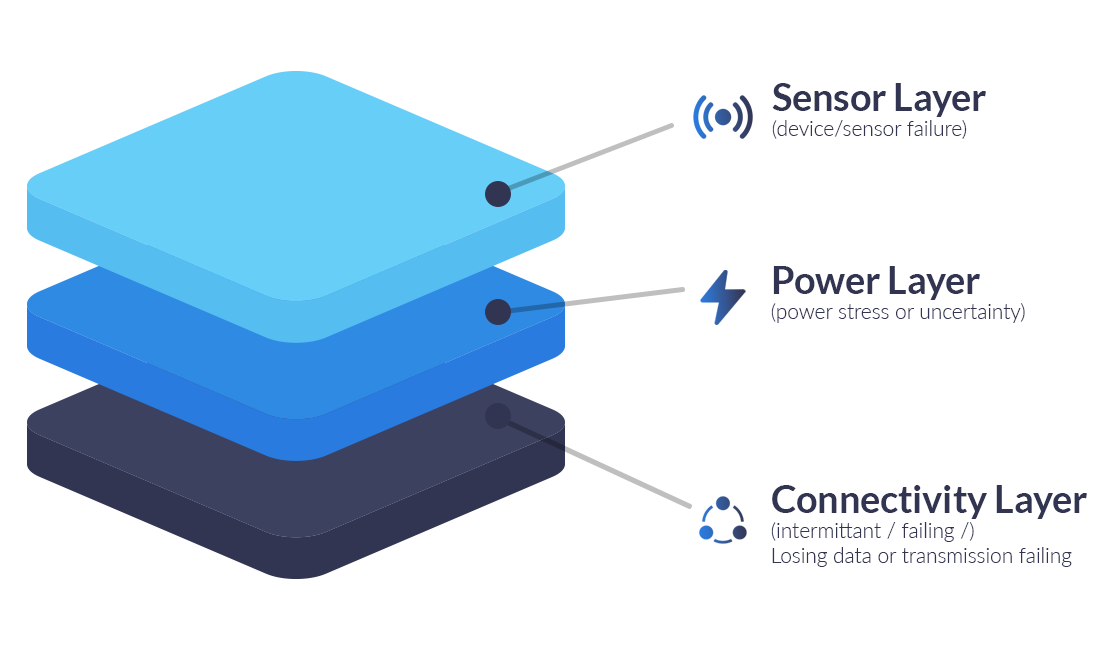

If you integrate remote environmental monitoring systems, you will eventually encounter a site where connectivity becomes the dominant uncertainty. Sensors continue to sample correctly. Local electronics remain operational. Yet data delivery becomes intermittent or unpredictable. In many cases, the issue is not outright loss of coverage, but changing network conditions at sites that were always near the edge of what terrestrial connectivity could reliably support.

At that point, the problem shifts. It is no longer about sensor selection or firmware optimization. It becomes a system design question: how do you maintain low power operation and predictable data delivery when network behavior cannot be assumed to be stable over time? This is where system integrators typically start comparing architectural options rather than individual bearers.

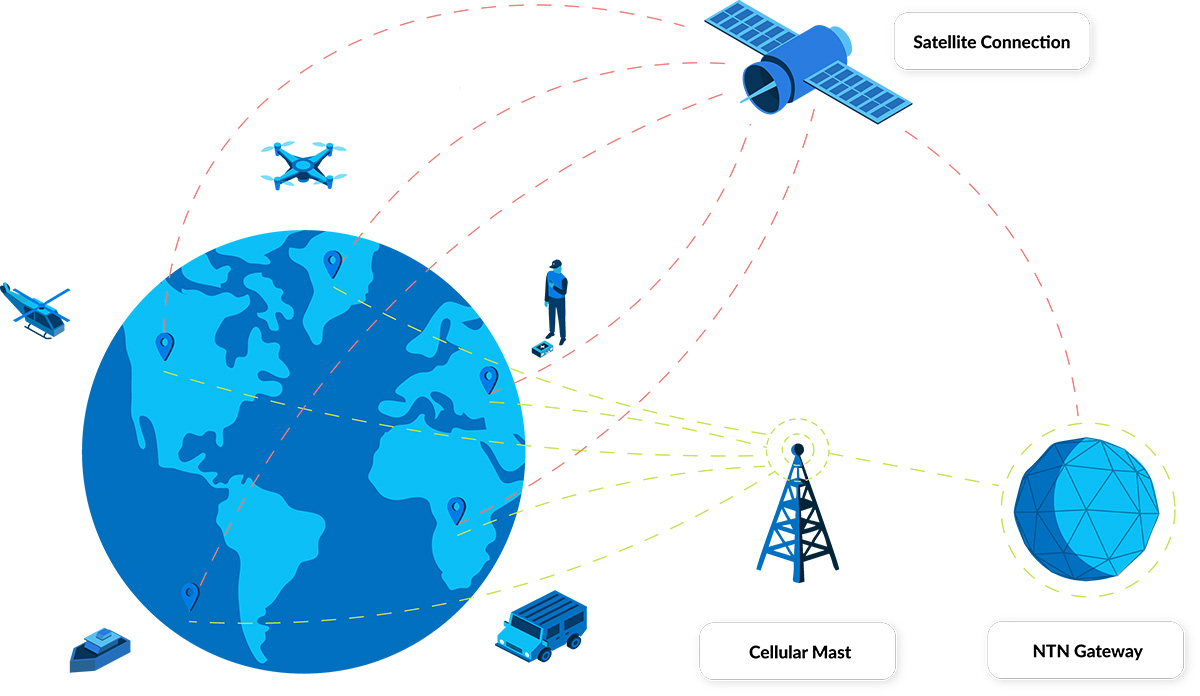

The first of these options is terrestrial cellular, using LTE-M or NB-IoT, where coverage is stable and well characterised over time. The second is proprietary satellite connectivity, where coverage reach and low duty cycle operation are prioritized over throughput. The third, emerging option is Non Terrestrial Network (NTN) NB-IoT, defined in 3GPP Release 17, which aims to extend cellular standards beyond terrestrial infrastructure using satellite networks.

Each model behaves differently at the system level. None is universally good or bad. The challenge for the system integrator is determining which operating envelope matches the realities of a given deployment.

A Practical Decision Framework for Remote Monitoring Sites

In practice, connectivity decisions are best framed around a small number of system-level criteria:

- How stable is coverage over seasons, vegetation cycles, and weather, not just at installation?

- How defensible does the connectivity choice need to be over a multi-year deployment?

- Is the team building a custom node, or does it prefer an integrated monitoring device?

- How constrained is power, and how expensive is site access if batteries deplete early?

- What is the expected payload size per reporting interval?

- How often does the device need to wake and transmit, and how tolerant is the application to latency?

In remote environmental monitoring, these questions are often more predictive of long term system than headline bandwidth figures or nominal coverage maps. They surface how connectivity behaves over time, how often radios wake, and how energy is actually consumed under real site conditions.

Technical Connectivity Matrix

The matrix below helps match connectivity options to their most defensible operating envelopes, and is most useful when applied to site conditions rather than connectivity technologies in isolation. In marginal or variable RF, devices may spend longer acquiring the network and retrying transmissions, which increases energy consumption and reduces delivery reliability / latency predictability. Those risks can matter as much as nominal coverage.

|

Cellular NB-IoT |

Proprietary Satellite* |

NTN NB-IoT** |

|

|

Primary Strength |

Lowest cost per KB; high throughput |

Global reach; predictable power profile |

Converged hardware model; emerging reach |

|

Coverage Stability |

Variable at cell edges; sensitive to vegetation |

High, assuming hemispherical sky view |

Emerging; constellation dependent |

|

Low Power Operating Modes and Sleep Opportunity |

Supports PSM (very low average possible), but sleep opportunity depends on operator timers + coverage |

Supports true deep sleep via power gating between scheduled bursts (system design dependent) |

Early estimates ~10–50 µA |

|

Transmit Load Profile |

TX current is variable (uplink power control, coverage enhancement). Worst case energy / on time can increase due to repetitions, attach / resume behavior, and retries |

TX is typically short burst transmissions with an implementation defined retry cap; peak can be amp class depending on module / rail, but event duration and attempt count can be tightly bounded |

Low power operation expected; current figures are highly implementation- and network-dependent |

|

Max Practical Payload |

1,400-1,600 bytes |

100 KB |

1,200 bytes |

|

Min Practical Payload |

30-50 bytes |

10 bytes |

10-30 bytes |

|

Typical Latency |

~100 ms to several seconds |

~10 seconds |

Medium (10 - 60s); MVNO scheduling could increase this to 2 - 5 mins) |

|

Risk Factors |

Network maintenance signalling and retries in marginal RF |

Relatively high peak current; antenna placement and sky visibility |

Immature ecosystem; coverage and delivery reliability still variable / under validation (latency and transaction timing may be less predictable than terrestrial) |

|

Deployment Status |

Mature and ubiquitous |

Mature and proven |

Early commercial trials |

*Based on Iridium Messaging Transport (IMT)

**Based on Viasat NB-NTN service – specification subject to change

Why Connectivity Dominates Lifetime Uncertainty

Long life environmental monitoring nodes are designed to sleep almost all the time because field power is expensive; whether that’s truck rolls for batteries or solar constrained by canopy, weather, latitude, and vandalism risk.

In most deployments, the sensing and compute workload is predictable and easy to budget. What’s harder to budget is communications: acquisition time, repetitions / retries, and delivery uncertainty can swing dramatically with site RF conditions and seasonality. That variability often becomes the biggest driver of both battery life uncertainty and operational reliability, more so than the sensor workload itself.

How Terrestrial Cellular Behaves in Remote Environments

Cellular connectivity performs well when coverage is stable and predictable. In those conditions, LTE-M and NB-IoT are often the most cost effective and operationally simple choice.

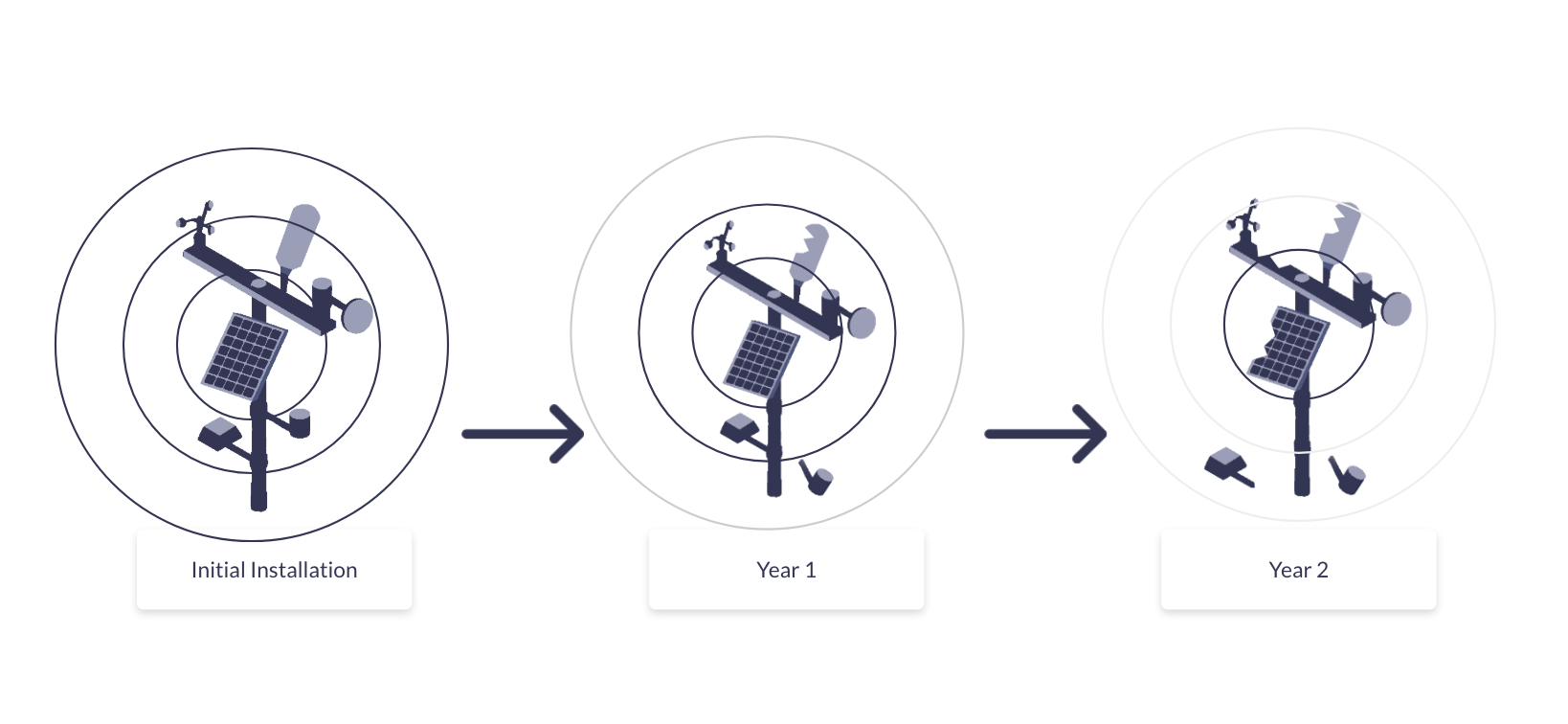

Challenges arise in remote environments where coverage quality fluctuates rather than failing completely. Field experience from utilities, water monitoring, and environmental telemetry deployments shows that link conditions at unattended sites often vary over time due to terrain, vegetation growth, weather, and seasonal effects, even when initial installation is successful.

From a power perspective, this variability matters. Under marginal coverage conditions, devices may attempt repeated attachment or transmission cycles before successful delivery. These retries consume energy without proportional data transfer.

Operationally, this can result in systems that appear functional but are difficult to predict. Batteries deplete faster than expected, and data gaps are harder to diagnose remotely. This does not mean cellular is unsuitable for remote monitoring. It highlights the importance of understanding how cellular behavior evolves within a specific deployment context, particularly at marginal coverage sites where energy risk can be as significant as coverage risk.

If your design needs predictable energy and diagnosability under uncertain RF, you may prefer a connectivity model that is explicitly scheduled and bounded: this is the key shift introduced by satellite IoT.

How Satellite IoT Architectures Change System Assumptions

Satellite IoT spans two broad architectural models: message-based services (store and forward / burst messaging) and IP-based services. Message-based links are naturally aligned to low duty cycles: devices wake on an application defined schedule to transmit a small payload, optionally open a short receive window, and then return to deep sleep. In this model there is no requirement for continuous “always-on” participation, and average energy use is closely coupled to reporting cadence, retry policy, and power domain design.

IP-based satellite terminals can provide richer connectivity and more interactive downlink, but may incur additional idle overhead to maintain readiness or session behavior, even when user traffic is low.

For long life environmental monitoring, the most defensible operating envelope is typically scheduled messaging with deep sleep between sessions, not continuous reachability. The remainder of this post therefore focuses on message-based satellite IoT, and on implementation patterns that make the comms link behave like any other managed subsystem with predictable states and budgets. We start with Iridium Messaging Transport (IMT) via RockBLOCK modules (particularly the 9704), as it fits naturally into a wake > transmit > sleep design.

Implementation path one: Message-based satcom as a managed subsystem (RockBLOCK 9704)

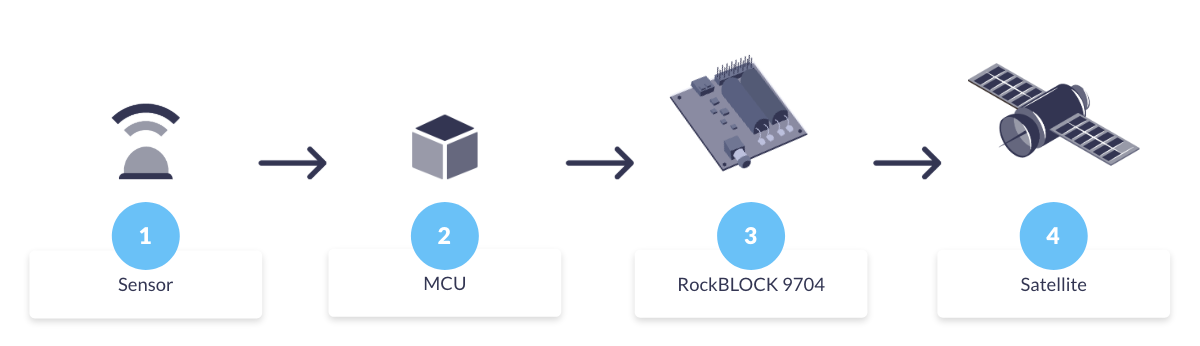

RockBLOCK 9704 is built around the Iridium Certus 9704 module and uses Iridium Messaging Transport (IMT): a cloud connected, two way messaging service for small to moderate payloads (up to ~100 KB) designed for IoT devices rather than continuous IP sessions.

In a long life monitoring node, it’s best treated as a schedulable subsystem inside a wider embedded design. In practice, integrators typically:

- Power-gate the modem (load switch/PMIC) so “off” is truly off

- Wake it only after sampling / validation, when there’s something worth sending

- Transmit in short, scheduled sessions, with an explicit retry policy

- Return to deep sleep (or fully unpowered) immediately after the exchange.

The key engineering advantage is boundedness: reporting cadence, session timing, and retry limits are largely under host control, so you can model energy around a small set of well defined states (off / boot / transmit / receive window).

Peak transmit current can be high because closing a link to a LEO constellation requires substantial instantaneous RF power. In a messaging oriented design this draw occurs in short, intentional transmit bursts with bounded duration. The design trade shifts from minimising peak current to ensuring the power system comfortably supports short peaks (battery internal resistance, regulator headroom, local capacitance), while keeping average energy dominated by how often you transmit.

RockBLOCK 9704 doesn’t manage your sensor rails or MCU sleep states – those remain the job of the embedded design – so standard low power techniques (switched sensor rails, unpowered analog front ends outside measurement windows) still apply.

Because IMT is a two way messaging service, you can make delivery outcomes explicit at the application layer: buffer locally, send, then check for confirmation on the next scheduled wake window, without keeping the node awake. This keeps reliability mechanisms aligned with the same duty cycled philosophy as sensing. The important caveat is that network availability (constellation / service uptime) is not the same as guaranteed delivery in every installation: local RF conditions still dominate, i.e. sky view, canopy, terrain, enclosure losses, and antenna placement.

That integration pattern works well when you’re building your own node around a messaging modem. When you’d rather avoid custom hardware and firmware integration, the same principles can be applied at the system level:

Implementation path two: RockBLOCK RTU as an integrated low power monitoring device

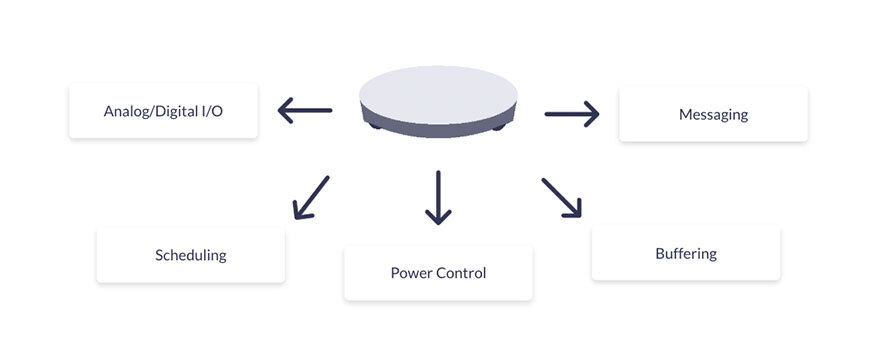

If you don’t want to integrate and power manage a satcom module inside your own node, RockBLOCK RTU packages the same sleep dominant principles at the system level: sensing, scheduling, local buffering, and messaging in one device. RockBLOCK RTU uses Iridium Short Burst Data (SBD), Iridium’s classic two way short-packet messaging service, so it naturally fits duty cycled environmental monitoring workloads.

RockBLOCK RTU is designed around a sleep dominant lifecycle:

- Extended low power sleep as the default state

- Wake events driven by schedule, thresholds, or external triggers

- Short transmission windows

- Immediate return to sleep.

Sensor power is explicitly controlled so sensors are energised only during measurement windows, eliminating standing analog bias currents. This mirrors best practice low power sensor design without requiring custom analog switching. Because message-based satellite operation can be scheduled without continuous reachability, RockBLOCK RTU avoids some of the standing ‘network-reachable’ overhead that can appear in terrestrial designs (depending on configuration and coverage).

In addition to sensing, RockBLOCK RTU provides system level control and observability that are often important in unattended deployments. Configurable digital outputs can switch sensor power rails or external loads, and analog inputs can monitor system voltages (battery, supply rails, excitation lines).

This enables remote verification of power health, detection of brownout conditions, and confirmation that sensors are energised only when expected, helping distinguish sensing issues, power delivery problems, and comms failures without site access.

Time Alignment and Operational Visibility

A recurring operational challenge in unattended monitoring is ambiguity: when data is missing, it’s often unclear whether the system failed to measure or failed to report. RockBLOCK RTU reduces this ambiguity with an internal clock and UTC-aligned timestamps (GNSS when available), making it easier to correlate measurements with expected reporting intervals and separate sensing gaps from delivery failures.

When Proprietary Messaging Satcom is Usually the Wrong Tool

Message-based proprietary satellite IoT is optimized for predictable, low duty telemetry – not high volume data or near real time streaming. Where cellular coverage is stable and power is plentiful, terrestrial LPWAN/cellular often remains the simplest and most cost effective option.

The interesting middle ground is NTN NB-IoT, which aims to extend cellular-style connectivity via satellite, so it’s worth understanding how much of the terrestrial behavior (and variability) it inherits.

NTN NB-IoT as an Emerging Option

Non-Terrestrial Network (NTN) NB-IoT, standardized in 3GPP Release 17, extends familiar NB-IoT device and core concepts to satellite links and is often framed as a bridge between terrestrial cellular and proprietary satellite IoT.

For environmental monitoring engineers, the key point is the capability shape: NTN NB-IoT is still fundamentally a low data, latency tolerant telemetry channel , not a streaming link , while aiming to preserve cellular style device models and tooling.

Commercially, it remains an emerging option: footprints, roaming models, and integration paths are operator and region dependent, and multi year public field data on power variance and failure modes is still limited compared with mature terrestrial PSM deployments. That doesn’t imply worse power performance; only that it’s harder (today) to treat it as a fully characterized default for unattended multi-year deployments.

As an illustrative example, Viasat’s NB-NTN positioning is bidirectional messaging with practical payloads around 10–30 bytes up to ~1,200 bytes, typical latency on the order of 10–60 seconds (potentially minutes depending on scheduling), and cost optimized for very small monthly data volumes (e.g., <50 KB).

One implementation detail worth flagging is NIDD (Non-IP Data Delivery). Where supported end to end by the operator and device stack, NIDD can reduce protocol overhead for tiny messages versus UDP/IP, which can materially help battery life at scale; but it’s worth confirming early whether your chosen NTN integration path actually exposes it in practice.

RockBLOCK RTU and NTN Evaluation Paths

An NTN-enabled RockBLOCK RTU is being used in early programs on Viasat’s NB-NTN service. The point isn’t that NTN performance is already fully proven; it’s that you can test and measure it using a monitoring device with a known low power architecture and good instrumentation.

Because RockBLOCK RTU already implements a sleep-dominant lifecycle (scheduled wake, short transmit windows, controlled sensor power, UTC-aligned timestamps, and supply-voltage monitoring), it provides a consistent baseline for evaluating NTN energy use, delivery timing, and variability without redesigning the sensing node.

If you’re considering NTN NB-IoT for an environmental monitoring deployment, Ground Control can support trial deployments and share an evaluation plan.

Practical Implications for System Integrators

For system integrators working in remote environmental monitoring, connectivity decisions are rarely static. Alignment between duty cycle, power constraints, coverage stability, and operational risk tends to determine long term system performance.

Cellular, proprietary satellite messaging services, and NTN NB-IoT each occupy different operating envelopes. Understanding those differences enables decisions to be defended throughout the lifecycle of a deployment.

Where coverage stability cannot be assumed, satellite connectivity provides an architectural alternative that aligns well with how low power remote monitoring systems are typically designed to operate. NTN NB-IoT represents a promising but still emerging option, particularly in contexts where long-term unattended power and reliability characteristics are still being established.

Planning for Intermittent Connectivity is a System Decision.

If you’re assessing where proprietary satellite, NTN NB-IoT, or hybrid connectivity fits into your architecture, we can help you evaluate the trade offs early, before reliability or power becomes the constraint.

Complete the form, or email hello@groundcontrol.com and we’ll reply within one working day.