Satellite IoT connectivity is moving from niche to mainstream, with some analysts projecting that the market will hit 41 million connections by 2030. When terrestrial networks are congested, disrupted, or simply unavailable, satellite can keep assets connected far beyond the reach of cellular and fiber. It can also reduce exposure to some internet facing risks associated with terrestrial ISPs, including DDoS attacks, ‘Man-in-the-Middle’ attacks, and DNS poisoning.

That said, satellite connectivity doesn’t automatically equal secure connectivity. Even when the satellite link itself uses strong encryption, the security outcome depends on the entire data path: device to satellite, satellite to ground, and ground to your application or cloud environment.

To further complicate matters, security questionnaires and vendor checklists often assume a familiar IP network connection. And that works, until you’re using a message-based satellite service (e.g. Iridium SBD / IMT, Viasat IoT Nano, Globalstar) for power efficiency, cost control, or intermittent coverage. The requirements haven’t changed. What changes is where the controls live and what “good” evidence looks like.

In this guide, we’ll walk through a practical security checklist for IP-based satellite IoT services first, then show how to evaluate security when the service is message-based, including how to translate the questions your security team is already asking into answers that actually fit.

With an IP service, satellite behaves like a conventional network link: your device sends standard IP traffic, and you can govern it using familiar enterprise controls: segmentation, routing policy, VPNs, and firewalling. This familiarity makes it easier to map an IP satellite service onto existing network security requirements without reinventing the questionnaire.

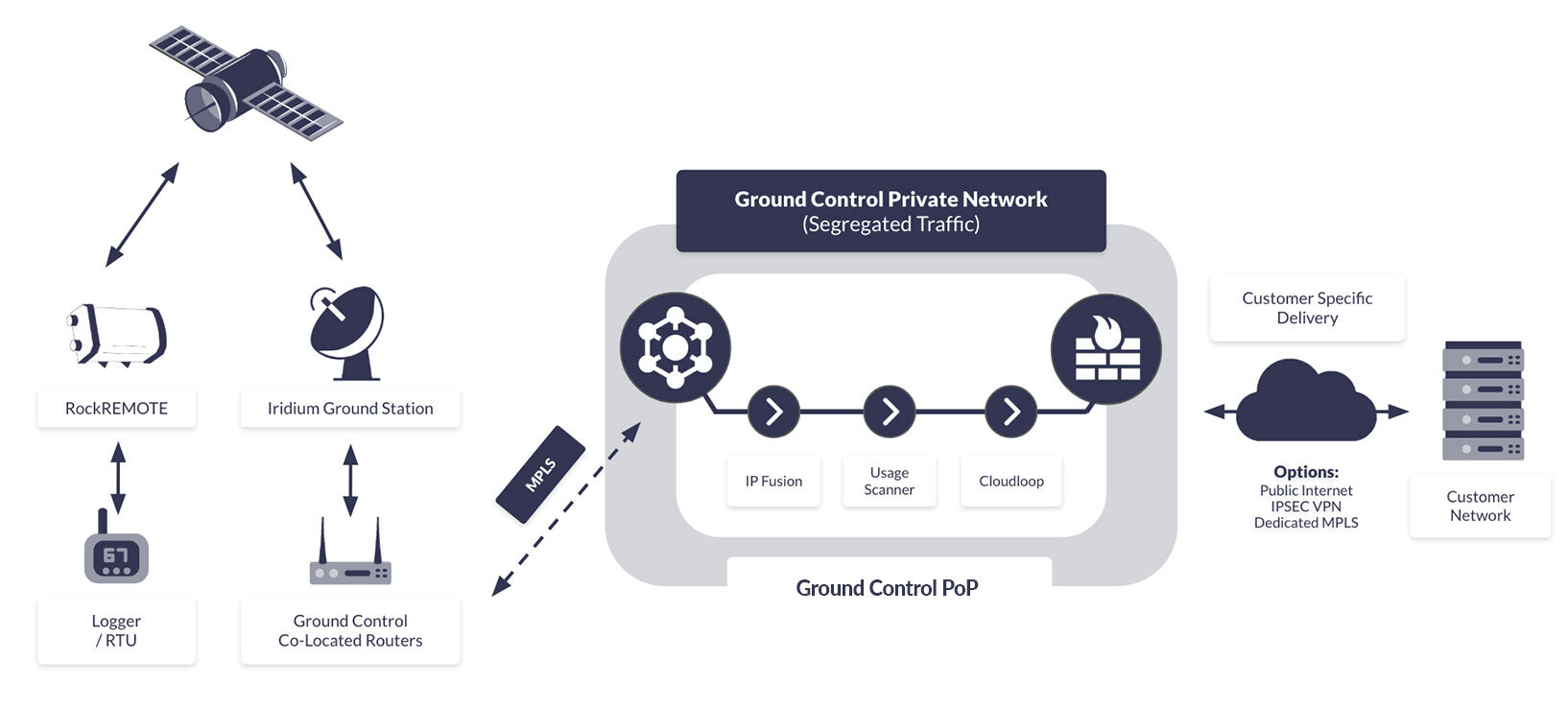

In practical terms, an IP design can offer clear control points. For example, in Ground Control’s Certus 100 IP architecture, traffic routes from the Iridium satellite network down to an Iridium ground station, then via dedicated MPLS into Ground Control’s Point of Presence (PoP).

From there, customer traffic can be matched to customer subnets and logically separated using mechanisms like policy routing.

For security conscious deployments, we recommend a VPN or MPLS between the PoP and the customer’s infrastructure; again, a control that fits cleanly into how security teams already think.

Messaging services, on the other hand, send discrete payloads instead of maintaining an IP pipe. We often describe this as being like a text message vs a telephone conversation. This changes where security teams should look for controls: instead of network layer tools like IPsec or inline inspection, the emphasis moves to device identity, payload production, ingress restrictions and cloud / message handling controls.

As mentioned, IP-based satellite IoT is often easier to get through security review because it behaves like a familiar network link, but the security outcome still depends on the full path: device → satellite → ground segment → onward routing into your application/cloud. In our 2025 “How Satellite IoT Connectivity Supports Data Security Measures” report, we emphasize that even when the satellite link itself is strongly encrypted, teams still need to pay close attention to the ground to application leg and the controls that protect it.

Here are six core controls most buyers should insist on for IP services, followed by two optional deep dives if your security team wants to go further.

1. Network path clarity (where does IP traffic go?)

What to ask: “Show the end-to-end IP path, including all handoff points and where the service terminates.”

What good looks like: A specific, documented route—device → satellite → ground → backhaul → PoP, so you can reason about trust boundaries, exposure, and where controls apply.

Evidence to request: A network / dataflow diagram + written description. For example, a Certus 100 IP route is described as device traffic going via Iridium satellites to an Iridium ground station (Arizona), then through dedicated MPLS to a Ground Control PoP in New York City.

2. Segmentation and tenant isolation

What to ask: “How do you ensure my IP traffic is isolated from other customers’ traffic?”

What good looks like: Traffic is identified (e.g., by customer-assigned subnets) and separated using standard network segmentation mechanisms that limit blast radius and cross-tenant exposure.

Evidence to request: A segmentation diagram + a plain-English description of enforcement. Customer traffic can be matched to customer assigned IP subnets and policy routed to dedicated VRFs, with separation maintained using policy routing.

3. Secure handoff into your environment (PoP → customer)

What to ask: “What secure connectivity options do you support from your PoP into our environment?”

What good looks like: A clear, security conscious handoff option that you can require in procurement; typically encrypted connectivity that avoids unnecessary exposure outside trusted networks.

Evidence to request: A supported connectivity options summary + where encryption terminates. For critical national infrastructure or security conscious use cases, we recommend a VPN between the PoP and the customer’s infrastructure.

4. Edge egress controls (firewalling + allowlisting)

What to ask: “What prevents a compromised site / device from generating unwanted traffic, and can we restrict outbound traffic to known destinations?”

What good looks like: Network level firewalling to block unnecessary protocols and reduce attack surface, and allow listing so only approved endpoints are reachable (limits exfiltration paths and unexpected chatter).

Evidence to request: Firewall and allowlisting capabilities + sample policy examples (even redacted). Ground Control’s RockREMOTE Rugged/Mini devices include an internal firewall that can block TCP/UDP/ICMP traffic. RockREMOTE Rugged can also block traffic from IP addresses, DNS ranges, or MAC addresses it doesn’t recognize.

5. Administrative access controls

What to ask: “How is administrative access protected and constrained (and how do you enforce least privilege)?”

What good looks like: Administrative access is gated (e.g., VPN), strongly authenticated, audit logged, and tightly authorized. This matters even if your IP data plane is isolated, because breaches often start in admin planes.

Evidence to request: An admin access model (roles, authentication, how access is granted/revoked). In our Cloudloop environment, AWS access is via client to site VPN.

6) Assurance and scope (certifications + what they actually cover)

What to ask: “What independent assurance do you hold, and what is in scope for this service?”

What good looks like: Relevant certifications / attestations plus clarity on scope. The goal isn’t a logo wall; it’s confidence that the environments and processes supporting your service are governed and audited.

Evidence to request: Certificates / attestations + scope statements. As an example, Ground Control aligns to ISO 27001, and our Cloudloop environment runs on AWS infrastructure with published compliance standards including ISO 27001/27017/27018.

Optional deep dives (add these if your security team wants extra assurance)

A) Internal segmentation to limit lateral movement (platform / network internals)

What to ask: “If a component is compromised, what prevents lateral movement to other services or environments?”

What good looks like: Clear internal segmentation with least-privilege network rules (subnets / ACLs / security groups) so only required traffic is allowed.

Evidence to request: A high level VPC / subnet diagram + explanation of east-west controls. In Cloudloop, applications are segregated by subnets / subnet ACLs, with communication controlled via security groups.

B) Transport security for exposed endpoints (TLS configuration + certificate lifecycle)

What to ask: “How are API / control plane endpoints secured in transit, and how are certificates managed and rotated?”

What good looks like: Modern TLS and a managed certificate lifecycle (rotation), so encryption isn’t “set and forget”.

Evidence to request: TLS policy summary + certificate management approach. In Cloudloop, the load balancer uses an auto-rotating TLS certificate via Amazon ACM, and the API is accessed over HTTPS with TLS 1.3 (backwards compatible to 1.2).

So far, everything we’ve covered assumes your satellite service looks like a familiar IP link, and for many deployments, that’s exactly right. But there’s a reason satellite IoT doesn’t always behave like terrestrial networking: a lot of field devices aren’t designed for always-on sessions or chatty protocols. In many real world deployments, the requirement is simply “send a small amount of data reliably, from anywhere, using as little power as possible”. That’s where non-IP, message-based services come in.

Even when an IP-based service is the right fit, it’s worth understanding why so many satellite IoT deployments don’t use IP end to end.

The simplest reason is that satellite data is still materially more expensive than terrestrial connectivity, so teams quickly become disciplined about how much they send and how often they send it. We recommend customers start by sizing the data requirement properly, and, where possible, use edge processing (for example, reporting by exception) because time spent minimizing data up front typically pays back in lower ongoing airtime usage.

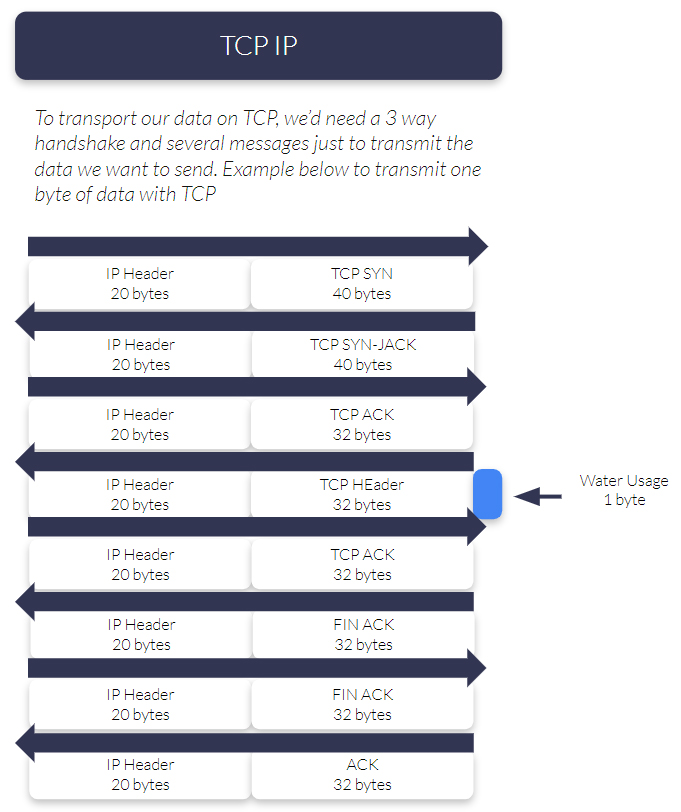

Then there’s the technical reality: TCP/IP can be inefficient for very small, infrequent transmissions. The protocol overhead (handshakes, acknowledgements, packet packaging) can mean you send far more than your actual payload, which you pay for, and which can cost power to transmit. That overhead isn’t usually a problem on a mains powered device, but it matters a lot for remote sensors expected to run on batteries for long periods.

That leads to a practical engineering question: can you optimize enough to avoid a full IP session? In our “IP vs Messaging” post, we outline a few common options teams explore when IP feels too heavy for the job: optimize transmissions, consider UDP/IP if the application can tolerate some loss, use more efficient IoT-oriented protocols (e.g., MQTT over TCP/IP), or move to a message-based service.

Message-based services exist because for many use cases you don’t need an “always-on pipe”; you need reliable delivery of small payloads. Historically, one trade off was message size: with Iridium Short Burst Data, for example, messages support payload sizes up to 340 bytes (Tx) and 270 bytes (Rx). Where message-based connectivity has expanded dramatically is with Iridium Messaging Transport (IMT): this enables messages up to 100KB, which opens up far more use cases (multiple sensors per message, compressed images, etc.).

Messaging is therefore often a deliberate choice to control power and cost when the payload is naturally bursty and delay tolerant. IP still makes sense when your application genuinely expects an interactive two way IP session (things like SSH, SFTP, sockets, or web style workflows); in those cases, an IP-based service like Iridium Certus 100 or Viasat IoT Pro is often the cleaner fit.

When your satellite IoT service is IP-based, most security requirements naturally map to familiar network controls: segmentation, VPNs, firewall policies, and monitoring around an IP pipe. But message-based services (SBD/IMT) don’t behave like a continuous network link; they move discrete payloads through a message handling workflow. That means some common IP-style questionnaire questions (like “Do you support IPsec?”) stop being the right way to test the outcome you actually care about.

The security goals themselves don’t change: confidentiality, integrity, authentication, and auditability still apply. What changes is where those controls live. In message-based architectures, the emphasis shifts away from network layer controls and towards (1) protecting the payload itself, (2) verifying device identity and message integrity, and (3) controlling who can inject messages and how messages are processed once they arrive. In other words: you’re not securing a pipe, you’re securing a chain of custody for messages.

With that in mind, here’s the messaging checklist we recommend buyers use, so you can answer security questionnaires without pretending your service is something it isn’t.

Message-based satellite services (such as Iridium SBD/IMT, or Viasat IoT Nano) are often chosen because they’re power- and cost-efficient for small, infrequent transmissions. The security goals don’t change, but the control points do.

To keep this non-repetitive, the list below focuses on what’s specific to messaging (rather than re-stating general cloud security hygiene you’ll see in any platform review).

1. Payload confidentiality (encryption strategy)

What to ask: “Is the message payload protected end to end, and who controls the keys?”

What good looks like: Sensitive payloads are encrypted at the application layer (device or application), with a clear key ownership, storage, rotation, and revocation model.

Evidence to request: A short encryption design summary: where encryption happens, where decryption happens, and how keys are generated, stored, rotated, and revoked.

2. Payload integrity + authenticity (tamper detection / proof of sender)

What to ask: “How do we verify messages are from the expected device and detect tampering?”

What good looks like: Messages include integrity protection (e.g., signing or message authentication) tied to device identity, so downstream systems can reject modified or spoofed payloads.

Evidence to request: A description of the integrity mechanism (signature/MAC), what is covered (payload + metadata), and how verification is performed server-side.

3. Anti-replay controls (prevent old messages triggering new actions)

What to ask: “What prevents replayed or duplicate messages from triggering actions?”

What good looks like: Messages include replay-resistant metadata (timestamp / sequence number / nonce) and server side checks with defined clock drift and retry rules.

Evidence to request: Anti-replay design summary + how duplicates are detected and handled.

4. Device identity + authorization (who can send what, and how you revoke)

What to ask: “How are devices uniquely identified and authorized, and how do we revoke a device quickly if it’s compromised or lost?”

What good looks like: Per device identity, least privilege authorization, and a straightforward revocation / offboarding path.

Evidence to request: Provisioning and offboarding workflow, credential lifecycle (rotation / revocation), and the tenant / isolation model at the device / message level.

5. Ingress restriction (who is allowed to inject messages)

What to ask: “Who is allowed to inject messages into the platform, and how is unauthorized ingress prevented?”

What good looks like: Message ingress is constrained to expected upstream sources, reducing the chance of third party injection / spoofing.

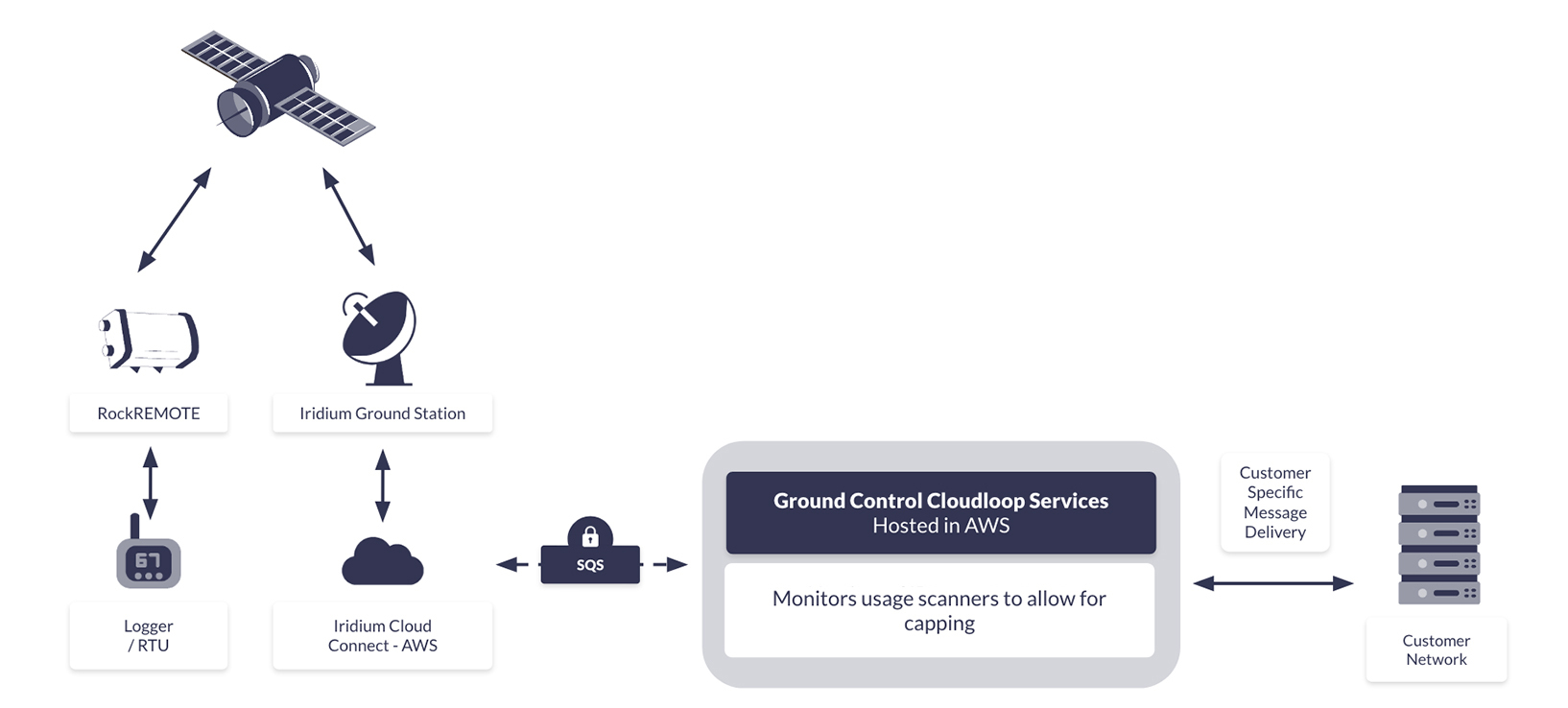

Evidence to request: Ingress policy summary and allowlist controls. In our Cloudloop Data environment, SBD ingress endpoints are restricted to Iridium.

6. End to end message path clarity (chain of custody)

What to ask: “Show the end to end message path, including where messages are terminated, queued, processed, and forwarded.”

What good looks like: A traceable chain of custody with clear trust boundaries and observable hops, so a buyer can evaluate risk and understand where to apply controls.

Evidence to request: A message flow diagram + written description. For example, in our Certus IMT flow, messages can travel device → satellite → ground station → Iridium CloudConnect (AWS) and then into our Cloudloop Data platform (AWS) via SQS.

Optional deep dives (only if your security team asks)

A) Transport security for exposed endpoints (TLS + certificate lifecycle)

What to ask: “How are platform endpoints secured in transit, and how are certificates managed and rotated?”

What good looks like: HTTPS/TLS with managed certificate renewal / rotation and modern TLS configurations.

Evidence to request: TLS policy summary + certificate management approach. In our Cloudloop Data platform, the load balancer uses an auto-rotating TLS certificate via Amazon ACM, and the API is accessed via HTTPS with TLS 1.3 (with TLS 1.2 support for compatibility).

B) Blast radius inside the processing layer (segmentation + least privilege)

What to ask: “If a component is compromised, what prevents lateral movement inside the processing environment?”

What good looks like: Clear segmentation and least privilege controls so only required service to service communication is permitted.

Evidence to request: High level segmentation summary + east-west restriction approach. In Cloudloop Data, applications are segregated by subnets / subnet ACLs, and inter-service communication is restricted using security groups.

IP and messaging are two transport patterns with different security control points. If your application needs interactive sessions and conventional network workflows, IP is often the cleanest fit. If your application is power constrained, bursty, and delay tolerant, messaging is often the right tool, but you’ll get a better security outcome by focusing on chain of custody, ingress restriction, and payload level guarantees rather than forcing IP-shaped questions onto a non-IP service.

A practical next step is to draw the end to end dataflow, mark every handoff point, and then gather evidence against the checklist that matches your transport. If your security team has an existing questionnaire, we can help map each IP-style requirement to evidence that actually fits either an IP or message-based architecture.

Map your security questionnaire to the right evidence

Security reviews move faster when the questions match the transport. Tell us what you’re deploying (IP, messaging, or both) and what your security team needs to see by emailing hello@groundcontrol.com, or by completing the form.

We’ll help map your requirements to clear control points and evidence, so you can progress procurement without forcing messaging into an IP-shaped checklist.